For Whom the Bell Tolls

| For Whom the Bell Tolls | |

|---|---|

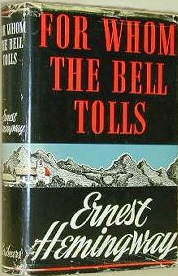

First edition cover |

|

| Author | Ernest Hemingway |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | War novel |

| Publisher | Charles Scribner's Sons |

| Publication date | 1940 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 471 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-684-83048-3 (Scribner's reprint) |

| OCLC Number | 34475606 |

| Dewey Decimal | 813/.52 20 |

| LC Classification | PS3515.E37 F6 1996 |

| Preceded by | The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories |

| Followed by | Across the River and into the Trees |

For Whom the Bell Tolls is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1940. It tells the story of Robert Jordan, a young American in the International Brigades attached to a republican guerilla unit during the Spanish Civil War. As an expert in the use of explosives, he is assigned to blow up a bridge during an attack on the city of Segovia. This novel is widely regarded to be among Hemingway's greatest works, along with The Sun Also Rises, The Old Man and the Sea, and A Farewell to Arms.[1]

Contents |

Origin of book title

The title of the book quotes John Donne's Meditation no. 17 from "Devotions upon Emergent Occasions" (1624): "No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee."

Plot summary

This novel is told primarily through the thoughts and experiences of Robert Jordan, a character inspired by Hemingway's own experiences in the Spanish Civil War. Robert Jordan is an American who travels to Spain to oppose the fascist forces of Francisco Franco.

A superior has ordered him to travel behind enemy lines and destroy a bridge, using the aid of a group of guerrillas who have been living in the mountains nearby. Robert Jordan encounters one of those in their camp, María, a young Spanish native whose life has been shattered by the outbreak of the war. His strong sense of duty clashes with both Republican partisan leader Pablo's fear and unwillingness to commit to a covert operation which would have repercussions, and his own joie de vivre that is kindled by his newfound love for María.

The novel graphically describes the brutality of civil war.

Characters in For Whom the Bell Tolls

- Robert Jordan – American university instructor of Spanish language and a specialist in demolitions and explosives.

- Anselmo: Elderly guide to Robert Jordan.

- Golz: Commander who ordered the bridge's demolition.

- Pablo: Leader of a group of anti-fascist guerrillas.

- Rafael – Incompetent, lazy guerrilla, and a gypsy.

- María – Robert Jordan's young lover.

- Pilar – Wife of Pablo. An aged but strong woman, she is the de facto leader of the guerrilla band.

- Agustín – Foul-mouthed, middle-aged guerrilla.

- El Sordo – Leader of a fellow band of guerrillas.

- Fernando – Middle-aged guerrilla.

- Andrés – Member of Pablo's band, brother of Eladio.

- Eladio – Member of Pablo's band, brother of Andrés.

- Primitivo – Young guerrilla in Pablo's band.

- Joaquin – Enthusiastic teenaged communist, member of Sordo's band.

Background

Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Cuba, Key West, and Sun Valley, Idaho in 1939.[2] In Cuba, he lived in the Hotel Ambos-Mundos where he worked on the manuscript.[3][4] The novel was finished in July 1940, and published in October.[5][6] The novel is based on his experiences during the Spanish Civil War, with an American protagonist named Robert Jordan who fights with Spanish soldiers for the republicans.[7] The novel has three types of characters: those who are purely fictional; those based on real people but fictionalized; and those who were actual figures in the war. Set in Andalusia, in the town of Ronda, the action takes place during four days and three nights. For Whom the Bell Tolls became a Book-of-the-month choice, sold half a million copies within months, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and became a literary triumph for Hemingway.[7] Published on 21 October 1940, the first edition print run was 75,000 copies priced at $2.75.[8]

Main themes

Death is a primary preoccupation of the novel. When Robert Jordan is assigned to blow up the bridge, he knows that he will not survive it. Pablo and El Sordo, leaders of the Republican guerrilla bands, see that inevitability also. Almost all of the main characters in the book contemplate their own deaths.

There is camaraderie in the face of death throughout the novel, with the need for surrender of one's self for the common good repeated. Robert Jordan, Anselmo and others are ready to do "as all good men should" – that is, to make the ultimate sacrifice. The oft-repeated embracing gesture reinforces this sense of close companionship in the face of death. An incident involving the death of the character Joaquín's family serves as an excellent example of this theme. Having learned of this tragedy, Joaquín's comrades embrace and comfort him, saying they now are his family. Surrounding this love for one's comrades is the love for the Spanish soil. A love of place, of the senses, and of life itself is represented by the pine needle forest floor – both at the beginning and, poignantly, at the end of the novel – when Robert Jordan awaits his death feeling "his heart beating against the pine needle floor of the forest."

Suicide always looms as an alternative to suffering. Many of the characters, including Robert Jordan, would prefer death over capture and are prepared to kill themselves, be killed, or kill to avoid it. As the book ends, Robert Jordan, wounded and unable to travel with his companions, awaits a final ambush that will end his life. He prepares himself against the cruel outcomes of suicide to avoid capture, or inevitable torture for the extraction of information and death at the hands of the enemy. Still, he hopes to avoid suicide partly because his father, whom he views as a coward, committed suicide. Robert Jordan understands suicide but doesn't approve of it, and thinks that "you have to be awfully occupied with yourself to do a thing like that."[9] Robert Jordan's opinions on suicide may be used to analyze Hemingway's suicide 21 years later. Hemingway's father also committed suicide and it is a common theme in his works.

The novel explores political ideologies and the nature of bigotry. After noticing how he so easily employed the convenient catch-phrase "enemy of the people", Jordan moves swiftly into the subjects and opines, "To be bigoted you have to be absolutely sure that you are right and nothing makes that surety and righteousness like continence. Continence is the foe of heresy."[10] Later in the book, Robert Jordan explains the threat of Fascism in his own country. "Robert Jordan, wiping out the stew bowl with bread, explained how the income tax and inheritance tax worked. 'But the big estates remain. Also, there are taxes on the land,' he said. 'But surely the big proprietors and the rich will make a revolution against such taxes. Such taxes appear to me to be revolutionary. They will revolt against the government when they see that they are threatened, exactly as the fascists have done here,' Primitivo said. 'It is possible.' 'Then you will have to fight in your country as we fight here.' 'Yes, we will have to fight.' 'But are there not many fascists in your country?' 'There are many who do not know they are fascists but will find it out when the time comes.'"[11]

Divination emerges as an alternative means of perception. Pilar, "Pablo's woman", is a reader of palms and more. When Robert Jordan questions her true abilities, she replies, "Because thou art a miracle of deafness.... It is not that thou art stupid. Thou art simply deaf. One who is deaf cannot hear music. Neither can he hear the radio. So he might say, never having heard them, that such things do not exist."[12]

Imagery

Hemingway frequently used images to produce the dense atmosphere of violence and death his books are renowned for; the main image of For Whom the Bell Tolls is the machine image. As he had done in "A Farewell to Arms", Hemingway employs the fear of modern armament to destroy romantic conceptions of the ancient art of war: combat, sportsmanlike competition and the aspect of hunting. Heroism becomes butchery: the most powerful picture employed here is the shooting of María's parents against the wall of a slaughterhouse. Glory exists in the official dispatches only; here, the "disillusionment" theme of A Farewell to Arms is adapted.

The fascist planes are especially dreaded, and when they approach, all hope is lost. The efforts of the partisans seem to vanish, their commitment and their abilities become meaningless. ", especially the trench mortars that already wounded Lt. Henry ("he knew that they would die as soon as a mortar came up".[13] No longer would the best soldier win, but the one with the biggest gun. The soldiers using those weapons are simple brutes, they lack "all conception of dignity"[14] as Fernando remarked. Anselmo insisted, "We must teach them. We must take away their planes, their automatic weapons, their tanks, their artillery and teach them dignity".[14]

Literary significance and critical reaction

Language

Since its publication, the prose style and dialogue in Hemingway's novel has been the source of controversy and some negative critical reaction. For example, Edmund Wilson, in a tepid review, noted the encumbrance of "a strange atmosphere of literary medievalism" in the relationship between Robert Jordan and Maria. [15] This stems in part from a distinctive feature of the novel, namely Hemingway's extensive use of archaisms, implied transliterations and false friends to convey the foreign (Spanish) tongue spoken by his characters. Thus, Hemingway uses the archaic "thou" (particularly in its oblique and possessive form) to parallel the Spanish pronominal "tu" (familiar) and "Usted" (formal) forms. Additionally, much of the dialogue in the novel is an implied direct translation from Spanish, producing an often strained English equivalent. For example, Hemingway uses the construction "what passes that" [16], which is an implied transliteration of the Spanish construction que pasa. This transliteration extends to the use of false friends, such as "rare" (from raro) instead of "strange".[17] In another odd stylistic variance, Hemingway referenced foul language (used with some frequency by different characters in the novel) with "unprintable" and "obscenity" in the dialogue, although foul language is used freely in Spanish even when its equivalent is censored in English (i.e. joder, me cago). The Spanish expression of exasperation me cago en la leche repeatedly recurs throughout the novel, translated literally as "I obscenity in the milk."

Narrative style

The book is written in the third person limited omniscient narrative mode. The action and dialogue are punctuated by extensive thought sequences told from the viewpoint of Robert Jordan. The novel also contains thought sequences of other characters, including Pilar and Anselmo. The thought sequences are more extensive than in Hemingway's earlier fiction, notably A Farewell to Arms, and are an important narrative device to explore the principal themes of the novel.

The plot is split into parallel actions at various points in the novel, including: the attack on El Sordo's band while Robert Jordan and company wait by their machine gun position, and, later in the novel, the preparations for the attack on the bridge and the course of Andrés, a guerillero who must take a message across the lines to a Republican general. While not an unusual narrative technique, it is a departure for Hemingway who, in his earlier works, preferred to maintain sharp focus on his protagonist. Some have argued that Hemingway was relenting to the demands of the Hollywood directors who wanted books more easily turned into scripts

Although most of the book is told from the point of view of people on the Republican side in the war, which clearly reflects Hemingway's own position, a notable exception is made in a single page giving the point of view of two soldiers of Franco's troops, who are shown as ordinary and quite sympathetic people, without an overt Fascist ideology – and whom Jordan is obliged to kill as part of the operation.

In 1941 the Pulitzer Prize committee for letters unanimously recommended For Whom the Bell Tolls be awarded the prize for that year. The Pulitzer Board agreed; however, Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University at that time, overrode both and instead no award was given for letters that year.[18]

Allusions/references to actual events

The novel takes place in June 1937 the second year of the Spanish Civil War.[19] References made to Valladolid, Segovia, El Escorial and Madrid suggest the novel takes place within the build-up to the Republican attempt to relieve the siege of Madrid.

The earlier battle of Guadalajara and the general chaos and disorder (and, more generally, the doomed cause of Republican Spain) serve as a backdrop to the novel: Robert Jordan notes, for instance, that he follows the Communists because of their superior discipline, an allusion to the split and infighting between anarchist and communist factions on the Republican side.

The famous and pivotal scene described in Chapter 10, in which Pilar describes the execution of various Fascists figures in her village is drawn from events that took place in Ronda in 1936. Although Hemingway later claimed (in a 1954 letter to Bernard Berenson) to have completely fabricated the scene, he in fact drew upon the events at Ronda, embellishing the event by imagining an execution line leading up to the cliff face.[20] In Ronda, some 500 people, allegedly fascist sympathisers, were thrown into the surrounding gorge by a mob from a house that faced onto the cliffside.

A number of actual figures that played a role in the Spanish Civil War are also referenced in the book, including:

- Andres Nin, one of the founders of the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), the party mocked by Karkov in Chapter 18.

- Prieto, one of the leaders of the Republicans, is also mentioned in Chapter 18.

- General José Miaja, in charge of the defense of Madrid in October 1936, and General Vicente Rojo, together with Prieto, are mentioned in Chapter 35

- Dolores Ibárruri, better known as La Pasionaria, is extensively described in Chapter 32.

- Robert Hale Merriman, leader of the American Volunteers in the International Brigades, and his wife Marion, were well known to Hemingway and served possibly as a model for Hemingway's own hero.

- André Marty, a leading French Communist and political officer in the International Brigades, makes a brief but significant appearance in Chapter 42. Hemingway depicts Marty as a vicious intriguer whose paranoia interferes with Republican objectives in the war.

Adaptations

- A film adaptation of Hemingway's novel, directed by Sam Wood, was released in 1943 starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. It was nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor and Best Actress; however, only the Greek actress Katina Paxinou won an Oscar for her portrayal of Pilar.

- A television adaptation, directed by John Frankenheimer, was broadcast in two parts on Playhouse 90 in 1956, starring Jason Robards and Maria Schell as Robert Jordan and Maria, with Nehemiah Persoff as Pablo, Maureen Stapleton as Pilar, and Eli Wallach as the gypsy Rafael.

- Another adaptation was made by the BBC in 1965 as a four-part serial (miniseries in American English).

- Also, Takarazuka Revue adapted the novel as a musical drama, produced by Star Troupe and starring Ran Ootori as Robert Jordan and Kurara Haruka as Maria in 1978.

Impact outside literature

The phrase "for whom the bell tolls" is often referenced in popular culture, although this may a reference to John Donne's poem as much as to Hemingway's novel. However, some usages have been explicitly based on Hemingway:

- "For Whom the Bell Tolls" is a song by Metallica on their 1984 album Ride the Lightning. It is about war and the human spirit, and is a reference to a chapter where El Sordo, another guerrilla leader, takes a position on a hill, surrounded on all sides, and he and his four comrades are killed by an airstrike. This is in the line "Men of five still alive through the raging glow, gone insane from the pain that they surely know." It was later covered by the four-piece cello band Apocalyptica.

- "For Whom The Bell Tolls" is a song by The Bee Gees on their 1993 album "Size Isn't Everything". The title is said to have come from the book in different interviews with Maurice Gibb.

Both main-party candidates in the 2008 U.S. Presidential election have praised the book. Democratic nominee President Barack Obama named the book as "one of the three books that have inspired him".[21] Republican nominee Senator John McCain named the book as his all-time favorite in an interview with Katie Couric on October 29, 2008. Additionally, the title for one of his own books, "Worth the Fighting For", (Random House, 2003), is a reference to protagonist Robert Jordan's thoughts to himself toward the closing of the novel.

Footnotes

- ↑ Southam, B.C., Meyers, Jeffrey (1997). Ernest Hemingway: The Critical Heritage. New York: Routledge. pp. 35–40, 314–367.

- ↑ Meyers 1985, p. 326

- ↑ Mellow 1992, p. 516

- ↑ One source, however, says he began the book at the Sevilla Biltmore Hotel and finished it at "Finca Vigia"

- ↑ Meyers 1985, p. 334

- ↑ Meyers 1985, p. 339

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Meyers 1985, pp. 335–338

- ↑ Oliver, p. 106

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest (1940). For Whom the Bell Tolls. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 338.

- ↑ For Whom (p. 164)

- ↑ For Whom (pp. 207, 208)

- ↑ For Whom (p. 251)

- ↑ For Whom (p. 330)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 For Whom (p. 349)

- ↑ Edmund Wilson, " Return of Ernest Hemingway" (Review of For Whom the Bell Tolls) New Republic, CIII (Oct. 28, 1940)

- ↑ E.g., For Whom (p. 83)

- ↑ M.R. Gladstein, "Bilingual Wordplay: Variations on a Theme by Hemingway and Steinbeck," The Hemingway Review, 26:1, Fall 2006, 81–95

- ↑ McDowell, Edwin. "Publishing: Pulitzer Controversies." The New York Times 11 May 1984: C26.

- ↑ In Chapter 13, Robert Jordan thinks "The time for getting back will not be until the fall of 37. I left in the summer of 36..." and makes allusion to the unusual June snowfall in the mountains.

- ↑ Ramon Buckley, "Revolution in Ronda: The facts in Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls", the Hemingway Review, Fall 1997

- ↑ LA Times

References

- Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (4th ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01305-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=yP-cgVNr55wC&printsec=frontcover&dq=isbn:0691013055&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

- Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-37777-3.

- Oliver, Charles M. (1999). Ernest Hemingway A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work. New York: Checkmark. ISBN 0-8160-3467-2.

External links

- Ernest Hemingway Website

- For Whom the Bell Tolls learning & teaching guide with themes, quotes, character analyses, multimedia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||